|

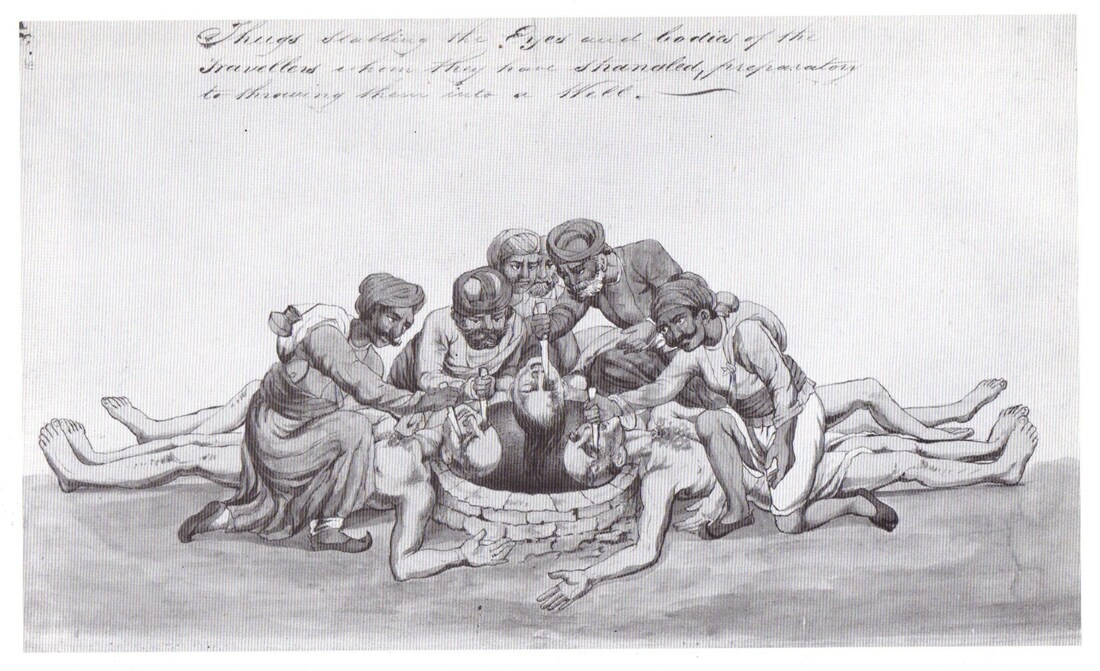

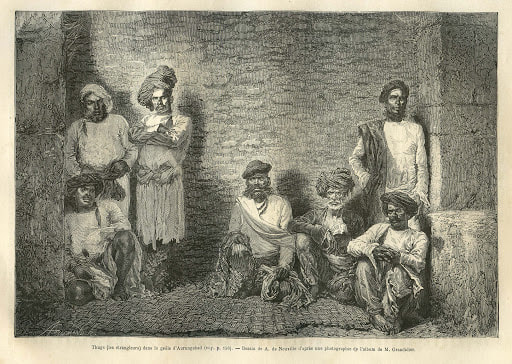

When we hear the word “cult” we often think of groups such as The Branch Davidians led by David Koresh or The Peoples Temple with Jim Jones at the helm. Some people would think of the Manson Family and Charles Manson. Others might think of organizations like Scientology or NXIVM, which operate somewhat as self-improvement programs with specific business models for making profit. We also tend to think of cults as a newer, more modern societal problem. In reality, cults have existed for many, many years. They’ve also existed around the world, not just in the United States. The formation of current general recognized religions notwithstanding, cults can be traced back to at least the mid-fourteenth century. One of the earliest documented cults was that of Thuggee. Active for about 400 years, their true impact wasn’t noticed by the masses until somewhere around the late 1700s or early 1800s (eighteenth or nineteenth century). Let’s start with some background because this isn’t the kind of cult that normally comes to mind when we think of such a group. The setting for this cult is in India, the vast subcontinent of Asia. In the mid-eighteenth century, the Mongol Empire (an Islamic dynasty that once ruled almost all of India at its peak) was quickly reaching a steep and slippery decline. Having become increasingly corrupt over its reign, the empire had become widely unpopular with the Hindu population. This caused many revolts and several regions had declared their independence. At the same time, Hindu rulers called the Maratha, who controlled most of central India by this point, began to grow increasingly aggressive and hostile while trying to keep their power. This regional political uprising deeply threatened the extensive profits of the British East India Company. (The British East India Company was formed by the British after taking over a vast amount of land in northern India and along its eastern coast.) In 1757, a combined force of British soldiers and recruited native citizens called sepoys defeated the Nawab of Bengal’s forces, leaving the British to rule the newly conquered territory. After passing the India Act of 1784 the British East India Company was formally transformed into an extension of the British government. This afforded British India more power and more land. Then, in 1803, British India attacked the two remaining prominent Maratha leaders. With the heavy leverage that winning that battle gave them, The British East India Company forced the surviving Maratha into an alliance under their rule. By now, the center territory of India is practically crime ridden and lawless, destroyed and demolished by decades of war. With everything in ruins, many are finding themselves without jobs and means of financial support for their families. In desperation and despair, many turn to robbery as a means of regular income and support in order to provide the mere necessities of life. Unfortunately, even with the vast wealth and land they are now in charge of, the British don’t want to invest the kind of money it would take to improve the local conditions in central India due to the severe increase in criminal activity. The most common kind of thief is called a dacoit. This is a particular kind of robber that targets travelers, the wealthy and occasionally entire villages. They are considered very dangerous and extremely ruthless, willing to kill if need be. However, they did not attack in their own villages and were in fact often revered in a Robin Hood type of sentiment as they would frequently disperse their spoils amongst the people in their village, providing much needed income and relief. However, by the early 1800s, a new variety of robber had surfaced. This new breed of criminals preferred strangulation as their main method of murder and they, without fail, always killed their victims which was unlike the dacoits who didn’t always murder. They more or less murdered as a last resort or a final means to an end. The first to be documented as coming across this brand of robber was British magistrate William Wright in 1807. As a group of men were arrested just by chance, some of the men chose to boast about being part of many killings, ultimately confessing to such crimes. This led Wright to curiosity and he began to build a sort of preliminary profile of the organization and its members. Wright found that this group (or gang), which had small active packs all throughout the territory, had their own slang language and had their own set of gang rituals and customs that they followed. Another surprising fact he learned was the amount of intelligence and forethought behind these types of killings. The murderers would slice their victims’ bodies open across the belly prior to burial. This was to reduce bloating and any amount of attention that may be drawn to the freshly buried corpses. In today’s investigative language, the killers were taking steps to counter forensic science and cover up or destroy evidence. This was both cunning and dangerous. It showed that they were intelligent enough to take countermeasures and that kind of intellect mixed with a criminal and murderous appetite make for an explosive combination, usually resulting in violence. Another tactic of this particular gang which was perhaps the most cunning and most dangerous of all was the behavior that led up to the killings themselves. Their most popular M.O. was to target a particular victim and then gain the victim’s trust. Often times the killers would travel some considerable distance with their intended victim. The way they would do this was extremely calculated. They would work as a team, starting with one posing as a fellow traveler having some sort of trouble. Their target would stop and offer assistance. The robber would then suggest that perhaps they might travel together to ward off marauders. Along the way of their travels they would pick up other gang members disguised as fellow travelers in need of assistance or protection. Once everybody was traveling together, the leader of the group would often use a ruse to get the victim into place, typically using an easily concealable length of cloth knotted at the ends (called a rhumal) to increase grip ability. Having the victim look up guaranteed an exposed neck plus increased the element of surprise. Then, after strangling the victim, they would slice the body, bury it and divide the profits.  Fast forward to 1808, another British magistrate named Thomas Perry arrives in northern India in the town of Etawah. This town turns out to be the flaming epicenter of a sprawling crime wave. Practically once a week, sometimes more, bodies were turning up in the wells that lined the roads leading into town. The bellies of the victims had all been sliced open. Additionally, it was clear that these poor and unfortunate souls were travelers as nobody in town knew them or identified them. With no way to solidify identification of the victims and no witnesses to any part of any crime, Perry could not arrest anyone for the killings. At this time, the British East India Company was set up and divided into three presidencies. This meant, of course, no one was sharing information with anyone else. In turn, this caused Perry to have no access to Wright’s notes and findings on the Thuggee group, even though it would have been incredibly helpful at the time. Perry decided to set up a checkpoint on one of the roads where a number of bodies had been discarded. Eighteen months later this led to the arrest of eight men. One man, Gholam Hossyn, gave his occupation as “Thug” upon questioning after capture. He eventually admitted to being part of more than ninety murders in the span of about three years or so. Other men of this group confessed to taking part in killings as well, one even laying claim to having personally strangled some forty-five victims himself. After learning that hundreds of Thugs in various gangs existed in and around Etawah, Perry set out to change things and his men arrested some 70 gang members. Those captured were sent to Bengal for trial. However, a particular requirement at that time for prosecution of crimes was a formal complaint to be filed by the victim’s family. Since the victims were travelers there were no family members to file such a complaint. Thus, the captured Thugs were acquitted. Also happening at the same time in 1808 is the arrival of William Sleeman. Sleeman decided to use the anti-Thug campaign as a way to make a strong name for himself and give himself notoriety. He developed a system to interrogate and flush out the remaining active Thugs. This system was so effective, it was soon adopted across India as general practice. Thugs who gave up information were labeled “approvers”. They were promised their lives would be spared IF they would give specific information as to names, dates, events, locations of bodies, etc. Now we are to 1812. Perry orders a group of British soldiers and sepoys to go to Sindouse, where intelligence has said is the base of operations for the Thuggee group. Apparently, this is where the Thugs have been able to operate with impunity and under the protection of a wealthy land owner naked Laljee. After many battles and lives and livelihoods lost, Perry is was able to drive the Thugs out of Etawah. Simultaneously, the East India Company still does not want to expend the resources for what they deemed a lost cause and a waste of funds and said resources. Worse yet, some British didn’t even believe that the Thugs and the Thuggee cult even existed. Eventually, having finally recognized the threat the Thugs posed to the fortune and power of the Company, they decide to share information and issue formal warnings to their men about the group. Fast forward again to 1829 and we come to the William Borthwick capture. British Officer William Borthwick convincingly lured seventy Thugs to a village near Indore (central India) and arrested them. Upon being detained, some confessed. Others did not. All this led to the new Governor-General of India to change policy, effectively allowing officers to pursue Thugs not only in their own territory, but in other native states as well if the need arose. In 1836, Sleeman is appointed Superintendent for the Suppression of Thuggee. He announced is success of the suppression four years later in 1840. His capture of Feringeea, one of the most successful Thuggee leaders, procured a wealth of information that led to the arrests of hundreds of Thugs. Various statements made by captured gang members about the depth of their belief, devotion and involvement led Sleeman to be convinced that these particular criminals could never be rehabilitated. Once imprisoned, they were never released. Not even the “approvers” were set free. During the suppression campaign somewhere around 4500 Thugs were brought to trial. Of this 4500 about 500 were hanged, the remainder sentenced to life in prison, somewhat on display like exotic animals or some kind of attraction. Some who were considered extremely unlucky were branded or tattooed with the word “THUG” and transported in chains and shackles to the worst penal colonies in all of the East Indies.  There is some controversy about whether this group was truly religiously motivated or if they were more crime and greed driven. They used their undying belief in Kali (the Hindu goddess of death and destruction, but also of creation) to justify their behavior and make themselves feel righteous. The word “thug” comes from the Hindi word “thag” which may quite possibly be derived from the Sanskrit word “sthag” meaning “to conceal”. The earliest reference to Thuggee is in the 14th century. However, most believe that gangs like what Perry encountered were around for about 150-200 years. Some oral traditions, folk tales and legends trace some Thugs back to seven original families from Delhi during the Mongol Empire and the reign of Akbar the Great. Those seven families fell out of favor and good graces of the Emperor. They were cast out and dispersed across the entire subcontinent as punishment.  Hindu God Kali Hindu God Kali Generally, the Thugs (even the Muslims among their members) worshipped the Hindu deity Kali. (This is the same group bad guys and the deity they worship in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, ya know, with the glowing sacred stones and the fire pit and all that Kali Ma chanting and ripping out hearts...yeah, that stuff…) The Thuggee group believed their actions were commanded by Kali and that they would not be punished for any of them. Considered to be deeply spiritual and very religious, Thuggees were always on the lookout for signs or omens from their deity Kali. These were usually found in the behavior of animals, like birds and such. Many of the followers considered their chosen profession a holy and honorable path which was virtually opposite from the dacoits. Although some were born into the life, others would adopt the lifestyle for a year or two in order to make ends meet. Plus, the Thugs had strict rules they were to follow that prohibited them from killing all women and foreigners, members of particular social orders, lepers and people they deemed crippled (presumably out of mercy, at least that’s my guess), goldsmiths, potters, oil venders (probably because they were merchants they needed to do business with), elephant drivers (yes, this is true, likely for the same reason as the merchants) and a plethora of others. (Additionally, in the cases where the followers did kill women, they never disrespected the women before dispatching them.) The Thugs had definite rituals they would perform before going out on what they deemed as missions. These rituals were usually done in prayer for strength, protection and guidance in the coming journey. Typically traveling in gangs of ten to forty men for each mission, the followers would sometimes reach numbers up to two hundred in order to complete a mission. At other times, different gangs would band together in order to pursue and achieve a bigger prize. Once the bounty was won, the spoils would be divided evenly amongst the group, which was typically fairly organized with a system and a method for stealing and killing. Their usual pattern would be:

Many times, the gang members would take on new roles or personalities to better fit in with their chosen target or targets, who would more often than not be people who looked like they had something worth taking. Though there were various methods of murder used throughout the 18th century including hanging and poison, the method of choice became strangulation by the 19th century. As stranglers, they would be known as bhutortes. Assistants to the bhutortes called shumseeas would hold the victim’s limbs during the attack to ensure little struggle. Finding suppression of the Thugs the perfect reason for trying to settle in India, the British soon used it as the main excuse for what they would deem altruistic means of imposition. Although the Thugs reported never actually attacked the British, they still seemed it necessary to protect themselves from the dangers of the gangs of Thuggee followers and their practices, eventually leading to the dissolution of the Thugs by the late 1830s. Recently, historians are starting to question just how organized this cult-like group actually was AND exactly how much of a threat they truly were. Just like anything else in history from that long ago, things can get, shall we say…misconstrued, over time. I wonder what the final determination will be. Thanks for reading!!! More to come!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThe Countess of the Crypt Archives

February 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed